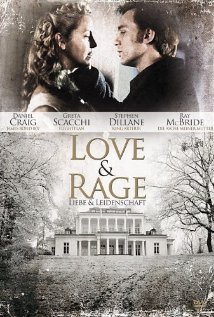

Love & Rage

script by Brian Lynch

1998

Feature film directed by Cathal Black, about the man who inspired Synge’s Playboy of the Western World.

Starring Greta Scacchi, Stephen Dillane, Daniel Craig (chosen in 2005 to be the new James Bond), Donal Donnelly and Valerie Edmunds.

Photographed by Slawomir Idziak (Three Colours Blue, etc)

The basis for my script is ‘The Playboy and the Yellow Woman’ by the distinguished Gaelic scholar James Carney. Carney’s book, which largely depends on a contemporary manuscript, tells the story of James Lynchehaun who was employed as land agent by Mrs Agnes McDonnell, the English owner of a large estate on Achill Island at the end of the 19th century. When she dismissed him he set fire to her house and attacked her viciously and sexually. After hiding out on the island for some six months, aided by his relatives, he was arrested and sent to jail for life. He escaped from Portlaoise Prison and fled to the United States where the Irish-American community resisted his extradition on the grounds that he was a rebel fighting against the English oppressor. The case reached the United States Supreme Court which eventually accepted that his offences were political and refused the extradition – a judgement with far-reaching consequences in the legal attitude to definitions of terrorism. Lynchehaun had some connections with the Irish republican Brotherhood, the IRB, but it seems clear that his grudge against Agnes was more personal than politicial. The script describes their relationship as an affair, but while there is some evidence for a more than business intimacy, the story I tell is purely imaginary.

The film was shot in the Valley House, on Achill Island, where the original events took place. The house, then a youth hostel, was transformed to a gloomy Victorian mansion in shades of brown and green to such effect that the owners wanted to retain it – and for all I know may have done so.

Additional footage was shot on the Isle of Man, which necessitated the movement of an enormous amount of equipment as well as of a crew and cast comprisng some one hundred people. This was just one of many factors that brought the producers to the brink of bankruptcy.

The worst result of the shortage of money and a tight shooting schedule – the film was shot in forty days – was that large chunks of the script were never shot.

For instance, the film was originally intended to begin with the riot in the Abbey Theatre on the first night of ‘The Playboy of the Western World’, during which the central character, James Lynchehaun, disguised as a priest (the sort of thing he did in real life) was supposed to congratulate Synge. Lynchehaun is referred to in the play as ‘the man bit the Yellow Woman’s nostril on the northern shore’ – this, in turn, is the culminating action in the film and in real life, an assault which led the Yellow Woman, Agnes MacDonell, to wear a silver nose. In a sense the entire film is a critique of the violent romanticism that underpins ‘The Playboy’, and I contrived the script in such a way to bring Synge and Lynchehaun face to face again at the end of the story – literally face to face in that Lynchehaun is in a position to give the artist a taste of his own medicine but, at the last moment, instead of biting his nose off, gives him a kiss. If this seems unlikely, unreal and bizarre it was meant to be, and in fact this is how I conceived the film as a whole: it was an exercise in impossibility, a test of the audience’s credulity, particularly as far as the character of Lynchehaun is concerned. In an earlier version of the script, for example, Lynchehaun seduces Agnes while he is dressedas a woman, a perverse joke that might have worked if the actor Cathal Black had chosen to play the part, a feminine-looking guy, hadn’t got cold feet and turned it down. There was, of course, no possibility of Daniel Craig passing himself off as a woman under any circumstances – Daniel is all animal man. He does, however, disguise himself as a clergyman and as Agnes’s upperclass English husband. Both disguises are so effective that I’ve met people who didn’t recognise him at all as the clergyman and, more explicably, didn’t realise he was pretending to be the husband – in the latter case you had to grasp that he has stolen a photograph of the husband and makes himself up using the photograph for the purpose. But that is by the way. In the event, Synge doesn’t appear in the film, so the literary subtext can only be grasped, if it can be grasped, by those who know that Lynchehaun is, partly, the inspiration for ‘The Playboy’.

Another example of how the script was curtailed: an important scene in the script shows Agnes returning to the Valley House after being raped by Lynchehaun in a hotel. She comes up the drive, enters the house, goes upstairs, runs a bath, changes her clothes and goes back into the bathroom, all the while engaging in dialogue with her maid Biddy, Valerie Edmunds, and her friend Dr Croly (Stephen Dillane). On the morning this sequence was to be shot, Cathal Black said he couldn’t do it – I reckon that, properly done, the sequence would have taken at least two days. So I took the script and, without even sitting down, reduced the scene to two camera set-ups, in the drive and in the doorway to the house. The latter scene, between Greta and Stephen, is very effective: in every rehearsal Greta cried, but in every take she could only act it – wonderfully well in my opinion. Indeed, I think her performance in the film is the best she has ever given in her career.

One final example, this time of editing: I myself played the part of Lynchehaun’s father (another variation of the film’s impossibilist theme) in a scene where he threatens his son with a loy, the kind of spade with which Christy Mahon, the Playboy, says he killed his father in the play. Slawomir Idziak contrived to shoot the scene, from under a black cloth, through a piece of thick distorted glass – Slawomir, or Swavek as his name is shortened in Polish, understood the intentions of the script very well and shot it, using a huge variety of his own hand-tinted lenses, in tones of green not unreminiscent, but less extreme, of Kieslowski’s ‘Short Film About Killing’. My memory of the shoot is that after repeated takes of me brandishing the dreadfully heavy loy I was so exhausted that I feared I was having a heart-attack. In the end the scene was left on the cutting-room floor.