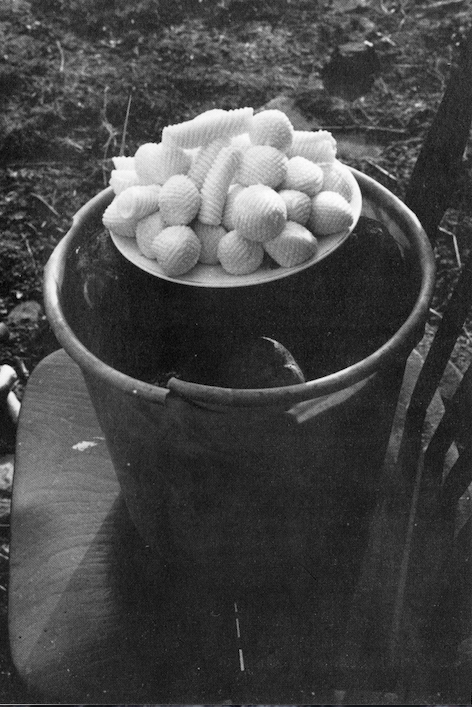

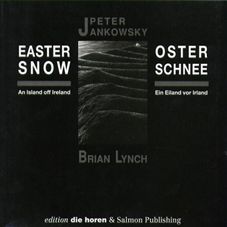

Bernie Winters, who died on 6 April 2015, aged 77, was the inspiration of this photograph and this poem, which appear in ‘Easter Snow/Oster Schnee’, a bilingual book co-published by Salmon, Galway, and die horen, Bremerhaven, in 1993. In a sense the entire book, which consists of photographs of Clare Island taken by Peter Jankowsky and his translations of poems about the photographs by me, was inspired by Bernie.

The Easter Present

‘Unrequited love’s a bore

But, for someone you adore,

It’s a pleasure to be sad’

The old song says, and that

Is enough for love – or is it?

Is it enough to fill with spuds

A plastic bucket – split at the brim,

Its handle broken off, filmed

With dust since water knows when –

And carry it down from your house

While balancing on their knobliness

A plate heaped high with butter –

As always the how throws a glancing

Light on why, as the rim of paint

On the delph, so worn away there’s

Almost nothing left of it, exposes

What time has done – and then leave it

As an Easter present for

The German couple and their boy

Outside the blue-painted door?

Is that enough? Perhaps it’s not.

And yet – seen through their eyes –

How could they requite it ,

Feeling a kind of despair that,

After all, they’re not just

Foreigners out here cut off

In the wild Atlantic, a kind

Of hope that can’t believe

It’s found a home this bright,

As mild and wide and clean

As Easter snow, beyond their grief,

Between the still searching air

And the thick butter’s moisture?

And yet it has – such is the gleam

Of giving – all the room in the world.

But no, it’s not enough. Allowed

To stand while cooling down,

The milk begins to separate,

Disproving with its yellowed cream

The golden rule of gravity:

What’s heavy does not sink,

It rises up, a thickening cloud

That floats on what is thin,

The greater weight of poverty.

You skimmed the surface then –

All this takes time of course –

And dashed its richness in

A churn until you got a fresh

And looseish droplet-beaded curd,

The colour of an apricot,

That’s good enough to eat.

Good enough to eat? No, it’s not enough

To simply mate it with the spuds,

These, now, opposites of flour

Humping their shoulders in the bucket.

No, you salt it first, the salt of earth,

In case it later gets too high and rots

Like apricots, like verse without

The grain of prose to make it last,

And then you play about with it, place it

Between two ridged, biscuit-coloured

Paddle-boards, and pat it into shapes –

Folded rolls and massy globes

Like gathered cones from soft firs.

And then, knowing it is not enough,

Fearing even perhaps, in the Irish way,

That it might well be too generous –

For us friendship is often too close

To sexual love for comfort –

You bring it to the German couple

And their child, leave it there

Without a word and then go back

To your own house and close the door.

No, don’t be sad, although

By now the Easter news is old

And unrequited love is a bore –

Not to have a second self to love,

To be alone when everyone else

In the wide world seems at home,

Kissed on the way in from work,

Talked to while getting washed,

Which you do silently, being fed

With butter and spuds and then –

If only you had someone to talk to –

After watching the late news on

Television going off together to bed

To do what they do in the city –

Still, in this case as in the blue song,

It’s pleasure enough just to shut the door,

To say I love you without self-pity

And be glad as ever Adam was before….

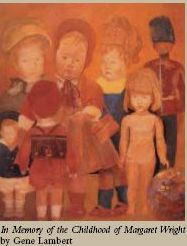

The German couple and their son referred to in the poem were Peter, who died on 17 September 2014, his wife the painter Veronica Bolay, and their son Aengus. One Easter morning they found this present of a bucket of potatoes and a plate of butter left outside the door of the cottage where they were staying on Clare Island. To Peter and Veronica this kind of anonymous generosity to strangers was a reason to come to live in Ireland, which they did. To me, a Dubliner who only visited Clare Island after most of the poems had been written, the photograph was primarily an aesthetic object, and the story attached to it seemed a reminder, a remnant, of an ancient tradition of hospitality, discoverable, if submerged, in all cities and countries, not confined to islands off Ireland, or other remote places.

But when I wrote the poem I hadn’t met Bernie. He was an invention of his gift.

When I did meet him in 1992, and on a few occasions thereafter, I began to understand how the trait of generosity was exemplified uniquely in his character. Does that character have any intrinsic connection with Ireland? I can’t answer that question. I do know Bernie was a highly intelligent person; a complex personality who lived, deliberately, a very simple life. A lover of nature, a lower-case Green, he appreciated modernity when it appealed to him. He loved, for example, the singing of that lone star of Texas, Nanci Griffith, who, Veronica has reminded me, he travelled to see performing at the Olympia Theatre in Dublin.

Bernie was – as who could not be living on an island? – an ironist, tempered by the weather. But, in the way he related to the world, there was a touch of the mystic about him. He was also an artist. Quite late in life he took up a tradition he had known since he was a boy – a tradition known indeed since the childhood of the human race – the weaving of objects out of straw, and made something new out of it. He had no pretensions: his craft was utilitarian. Ostensibly, he produced things that could only be used: sugán chairs, baskets and such like. But the ostensible does not conceal the artistic instinct the craft allowed to emerge. One of these pieces, supposedly a place mat, I have hung on a wall beside a window in my flat where it shines back at the sun it resembles. More of these objects, which have a sculptural quality, can be seen in the memorable photograph by Michael McLaughlin that accompanies the piece about Bernie published in the Mayo News on 14 April. See:

http://www.mayonews.ie/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=21763%3Aclare-island-mourns-local-legend&catid=23%3Anews&Itemid=46#

Bernie held the key to the Cistercian abbey just a few yards away from his house at Cille on the island. When Peter first brought me there no key was needed: the building was open to the four winds and all that could be seen on its vaulted, rain-sodden ceiling was a few faint streaks of pigment, remnants (that word again) of what had once, some 700 years earlier, been paintings. They were a melancholy sight, glimpses of a former world on the brink of complete extinction. Now, after years of work, mainly by Christoph Oldenbourg and Madeleine Katkov, they have been restored and, at least in part, returned to their original state. See the images at:

http://www.clareisland.info/Heritage/iconography.htm

But they remain to be explained fully. And these days one needs permission to gain access to the abbey. In a way the frescoes are like Bernie in reverse: he can’t now be visited and he has taken the key to his life with him, leaving traces only in the memories of those who knew him, and a few things made out of straw. This should be melancholy, and it is, but it isn’t sad only. There is as well in the thought of his gift a remaining and abiding freshness, the late present of an Easter Snow.